My Genealogical Data Pipeline

A while back I started doing some genealogical research as a kind of pastime. At some point during this journey, I discovered that my Great-Aunt Ruth’s had kept a database of genealogical data in some old, proprietary software. I didn’t have any desire to buy said software, so I asked if there was anyway that the data could be exported. My cousin, Dave, replied that it could exported as a gedcom file. He sent me such a file.

A gedcom file (for a full explanation see link), is a format invented by the Mormon church to store genealogical data. It’s plain text document that looks kind of like COBOL. It’s rather inscrutable.

Luckily there is a python library named python-gedcom that can parse just such a file. Whatever I’m going to do next while dealing with the gedcom file is based on the documentation of the python-gedcom library linked above.

What I wanted to in particular, was do extract the genealogical data, such as parents, siblings, children, birth years, and death years - but, more importantly, to get Aunt Ruth’s notes on relevant people. Aunt Ruth was a very smart an accomplished lady, she was a practicing psychologist in New Mexico and was an expert researcher - so her notes were the real prize! I decided I wanted to extract the data and perhaps upload it to a database for research purposes. Usually, my go to db is postgresql, but as this was genealogical data, which I thought lent itself particularly well to a graph database, and it’s just for fun, I figured I’d try out Neo4j.

I did this in a a Google Colab notebook. So the first thing I did was put my gedcom file in Google Drive and mount that drive. This was done like this:

from google.colab import drive

drive.mount('/content/drive')

You also need to install the python-gedcom library:

!pip install python-gedcom

Next I made an instance of a gedcom parser instance, parsed said gedcom file, and got a list of all the root child elements of the gedcom file.

One thing I discovered is that a gedcom file has several types of elements. I wanted to first filter out the elements representing people, so I made another list, only containing individual people:

from gedcom.parser import Parser

from gedcom.element.individual import IndividualElement

gedcom_parser = Parser()

# Example of data being parsed with 'False' to disable strict parsing.

# if you want strict parsing, just don't put in a second argument.

gedcom_parser.parse_file('content/drive/My Drive/path_to_my_file.ged', False)

root_child_elements = gedcom_parser.get_root_child_elements()

individual_elements = [element for element

in root_child_elements

if isinstance(element, IndividualElement)]

I also discovered that each gedcom element has it’s own unique id, called a “pointer” (maybe has something to do with the implementation - like a pointer in memory?). These pointers are how other elements are referenced. As such, I needed an easy way to find an element given a pointer. As such, I made the following dictionary:

indexed_elements = {e.get_pointer(): e for e in root_child_elements}

Then I made a function for getting the data I wanted from the gedcom file:

def get_personal_data(person: IndividualElement) -> dict:

first_name, last_name = person.get_name()

father, mother = [None, None] # In case there are no parents

parents = gedcom_parser.get_parents(person)

notes = None # In case there are no notes

if len(parents) == 1:

father = parents[0].get_pointer() # override None for father

elif len(parents) == 2:

father, mother = [p.get_pointer() for p in parents]

# Check here if Aunt Ruth had notes on this person ;)

for child_element in person.get_child_elements():

if child_element.get_tag() == "NOTE":

note_pointer = child_element.get_multi_line_value()

notes = indexed_elements.get(note_pointer).get_multi_line_value()

return {

"_id": person.get_pointer(),

"first_name": first_name,

"last_name": last_name,

"father": father,

"mother": mother,

"birth_year": person.get_birth_year(),

"died": person.get_death_year(),

"burial_data": person.get_burial_data(),

"birth_data": person.get_birth_data(),

"notes": notes

}

Next, I went through all the individuals and put them in a pandas data frame like this:

import pandas as pd

data = [get_personal_data(person) for person in individuals]

df = pd.DataFrame(data)

df.set_index("_id")

At this point, I already had a dataframe with a lot of info, and all of Aunt Ruth’s notes on each person.

Here’s an example of an entry of a person with Aunt Ruth’s notes in the dataframe:

| _id | first_name | last_name | … | notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| @I1@ | Avraham Gershel | Slutsky | … | The American great-grandchildren of Avraham Slutsky were told that their parents came from Russia. On all of the documents (e.g. marriage certificates, naturalization papers, death certificates) that we have, Russia is listed as their country of origin. However, Eugene Sloutsky who lives in Moscow and Mikhail Belikov, son of Chaya Ita Slutsky Belikov, (he also who lives in Moscow), tells us that the family came from Parafievka in Chernigov Gubernia, Ukraine. Teresa told her daughter that they came from Chernigov Gubernia… |

Then I exported the the data frame to CSV file in my Google drive:

df.to_csv("/content/drive/My Drive/aunt_ruths_notes.csv")

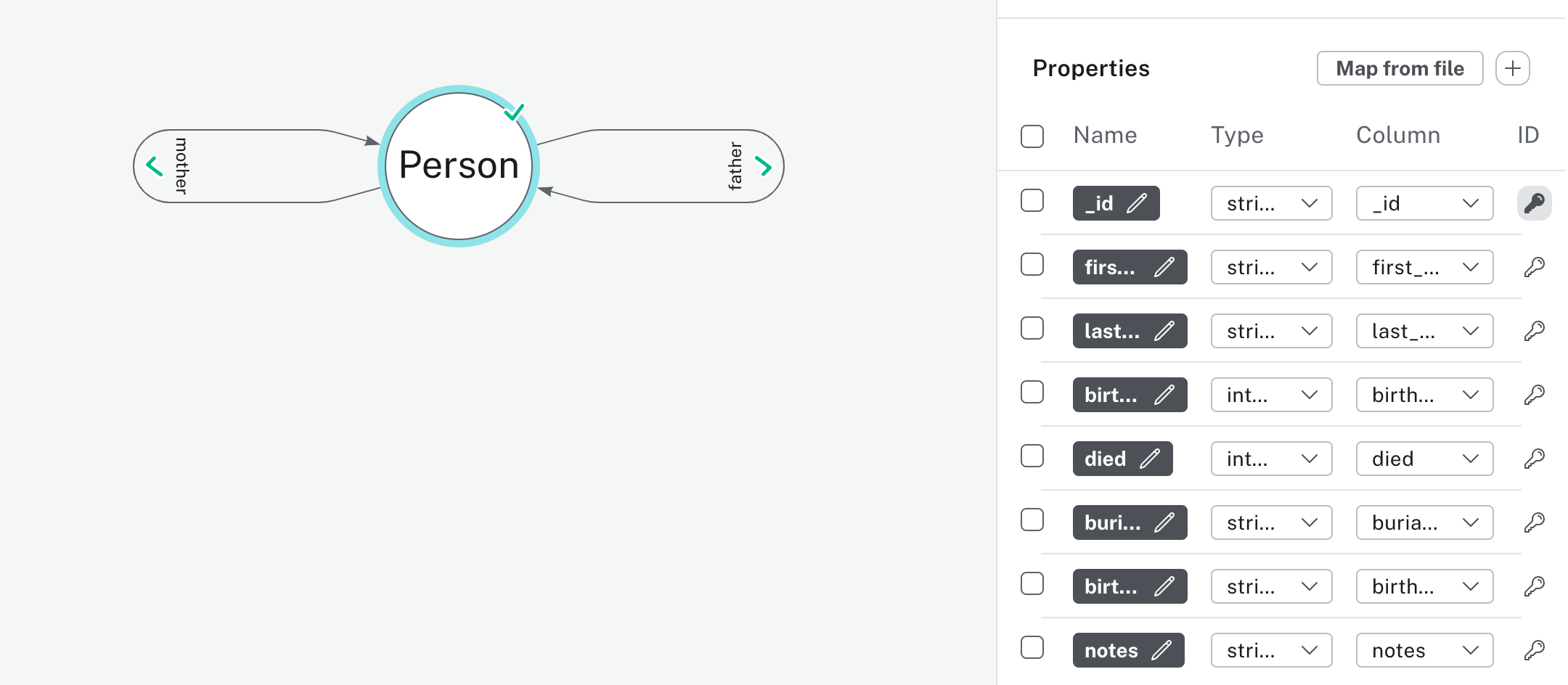

The next step is was to make an instance of AuraDB, a full managed graph database from Neo4j. Once you’ve gotten the instance going I used the CSV to make a data model. I used their graphical importer. I created a model called Person and I imported all the fields in the CSV except for mother and father as parameters, and then made a relationship called :mother and :father and had them point to the ids of the mother and father field. Like this:

I checked the code it generated, out of curiosity, and it generated this code. It was actually very informative.

:param {

// Define the file path root and the individual file names required for loading.

// https://neo4j.com/docs/operations-manual/current/configuration/file-locations/

file_path_root: 'file:///', // Change this to the folder your script can access the files at.

file_0: 'aunt_ruths_notes.csv'

};

// CONSTRAINT creation

// -------------------

//

// Create node uniqueness constraints, ensuring no duplicates for the given node label and ID property exist in the database. This also ensures no duplicates are introduced in future.

//

//

// NOTE: The following constraint creation syntax is generated based on the current connected database version 5.15-aura.

CREATE CONSTRAINT `imp_uniq_Person__id` IF NOT EXISTS

FOR (n: `Person`)

REQUIRE (n.`_id`) IS UNIQUE;

:param {

idsToSkip: []

};

// NODE load

// ---------

//

// Load nodes in batches, one node label at a time. Nodes will be created using a MERGE statement to ensure a node with the same label and ID property remains unique. Pre-existing nodes found by a MERGE statement will have their other properties set to the latest values encountered in a load file.

//

// NOTE: Any nodes with IDs in the 'idsToSkip' list parameter will not be loaded.

LOAD CSV WITH HEADERS FROM ($file_path_root + $file_0) AS row

WITH row

WHERE NOT row.`_id` IN $idsToSkip AND NOT row.`_id` IS NULL

CALL {

WITH row

MERGE (n: `Person` { `_id`: row.`_id` })

SET n.`_id` = row.`_id`

SET n.`first_name` = row.`first_name`

SET n.`last_name` = row.`last_name`

SET n.`birth_year` = toInteger(trim(row.`birth_year`))

SET n.`died` = toInteger(trim(row.`died`))

SET n.`burial_data` = row.`burial_data`

SET n.`birth_data` = row.`birth_data`

SET n.`notes` = row.`notes`

} IN TRANSACTIONS OF 10000 ROWS;

// RELATIONSHIP load

// -----------------

//

// Load relationships in batches, one relationship type at a time. Relationships are created using a MERGE statement, meaning only one relationship of a given type will ever be created between a pair of nodes.

LOAD CSV WITH HEADERS FROM ($file_path_root + $file_0) AS row

WITH row

CALL {

WITH row

MATCH (source: `Person` { `_id`: row.`_id` })

MATCH (target: `Person` { `_id`: row.`mother` })

MERGE (source)-[r: `mother`]->(target)

} IN TRANSACTIONS OF 10000 ROWS;

LOAD CSV WITH HEADERS FROM ($file_path_root + $file_0) AS row

WITH row

CALL {

WITH row

MATCH (source: `Person` { `_id`: row.`_id` })

MATCH (target: `Person` { `_id`: row.`father` })

MERGE (source)-[r: `father`]->(target)

} IN TRANSACTIONS OF 10000 ROWS;

I then had all the people in my family loaded into a Neo4j graph database. But this is where my lack of experience with graph databases really came in.

Some Mistakes I Made #

I’ve been playing around and I think that having the notes as a parameter in the Person model was a bad choice. I should have made Notes it’s own model. Then I could include things like the Author, and connect the notes to multiple people. For example, sometimes at Ruth will have note on person X which just says “see note on person Y” - it would be much better to connect the same note to both people. Also, Aunt Ruth attributes various things to various people. That could be another thing. Another mistake I made was forgetting to extract the gender data in my original get_personal_data function. So while I’ve already had a lot of fun learning cypher and researching the data, I think I’m going to redo the data modeling in Part II.